"A lot of inexperienced people go cruising before they know what they're getting into."Robin Lee Graham was all of sixteen when he sailed out of San Diego on a solo trip around the world. By the time he wrote the words above, he was nineteen years old and had more sailing experience than most of us will get in a lifetime.--Robin Lee Graham, April 1968.

Graham's voyage, captured in two National Geographic cover stories and a book, begs the question: which should we admire more, the boldness of youth or the cautious wisdom of experience? Just how much experience does a sailor need to leave port?

Like many cruisers, we struggled with the issue of when we would be competent to venture out into the larger world. The boat was ready, but were we? In fact, the year before we left we spent so much time working on the boat that it seemed we rarely left the dock, much less took the shakedown cruises we had envisioned. For years we had sailed almost every weekend on Tennessee lakes, but never in the ocean. We had the benefit of a couple of Power Squadron classes, but the longest cruise we had ever taken was a whopping five days long.

Some people spend years getting ready to cruise, and that's a prudent way to go about it. They take classes and gather certifications from basic sailing to coastal cruising and offshore passagemaking, crew on delivery trips, read books on heavy weather tactics and lie awake at night thinking about man overboard drills. Others, most of whom seem to be around twenty years old, just jump in a boat and head for the South Pacific. Until the day he set off in the first solo nonstop around the world race in 1968, Chay Blyth may have never sailed a boat before in his life! There are those who stick to protected water, keeping the time they are out of the sight of land to a bare minimum--for the longer you are out there, the more sure you are to encounter nasty weather--but then there is Reid Stowe, who plans to spend 1,000 uninterrupted days at sea, Waterworld style, in his 70 foot schooner (see www.1000days.net).

I knew that my little family on our small boat, a 35 foot S2 center cockpit sloop, would never cross the Pacific or sail around the world. Neither our boat nor our family were designed for that kind of cruise. We wanted to cruise the coastlines, island-hop around the Bahamas and Caribbean, learning as we went. Privately, I wanted to get down as far as the Virgin Islands, as if that was some sort of benchmark. In the end we made it as far as the Dominican Republic, which gave us more than enough of a fair taste of isolated passages.

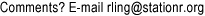

Fortunately, driving a boat down the ICW and across the Gulf Stream to the Bahamas has gotten a lot easier over they years. When we were in the Exumas last winter, I reread Dove, the classic story of Graham's teenage circumnavigation. In 1968, he was in the Bahamas, visiting some of the very same places we did, yet in many ways he was in another world. He didn't have guidebooks telling him exactly where to anchor, a GPS with his exact location, beautiful and amazingly accurate color charts, and weather gurus advising when to move and when to stay put. These days, we don't exactly cruise in the manner of Columbus, who incidentally nagivated these same waters with amazing success even though he thought he was making landfalls in China and Japan. Not to say that you can't still lose a boat on a reef (as Columbus did with the Santa Maria), but in comparison cruisers today have a lot of help. Experts such as Bruce Van Sant and Stephen Pavlidis write books that give us strategies and routes; weather gurus such as Chris Parker provides personalized forecasts of wind and seas. And like other cruisers, we often travel with other boats, lights on the horizon and voices on the radio during those overnight passages, ready to assist one another if needed.

Have we made cruising so easy that it has lost its sense of adventure? I don't think so. Venture south of George Town in the Bahamas, and you will be pretty much on your own. There are islands such as Samana where you may be the only people for fifty miles, tucked inside a reef that can be entered only with great skill, great luck, or perhaps some of both. We may speak with some disdain of the habit of visiting only "guidebook approved" places, but should also remember that last winter two cruising catamarans were lost in one night when they went beyond the guidebook routes and were caught on the wrong side of Mayaguana by a strong cold front (see Kismet Log 22 and Log 23). There is plenty of danger and adventure still out there in the world.

Most cruisers start out with coasting cruising, even if they are just making their way south to start their "real" trip to the islands. On the ICW and in near-shore waters, the Coast Guard, towing services, and other sources of help are just a radio or cell phone call away. You might suffer embarassment or a towing bill, but reasonable care and a watch on the weather make the chances of losing your vessel low. Once you venture more than about fifty miles from the U.S. coastline, the equation changes dramatically. Weather forecasts are not easily received; cell phones stop working. An EPIRB or satellite phone becomes your best bet for summoning help. You can't count on outside assistance and must be able to handle most problems on your own. On the bright side, until you're offshore for more than a day or two, you should be able to avoid any really nasty weather. With a little luck and a little mentoring from other boats you meet along the way, most people are ready for the islands by the time they get there.

We were "ready" when we left home? Maybe not, but we had the right attitude. We knew we had a lot to learn (we still do!) and that's an important concept for anyone who wants to sail a boat anywhere out of familiar waters. Learning to cruise a sailboat for most people is, quite literally, like hopping down a chain of islands--one baby step at a time. My wife Annie, who at one time had declared, "But I don't want to live on a boat!" was finally convinced by a large scale map of the Caribbean I had put up on the wall. We could cover thousands of miles without ever being more than a day's sail from land.

"We can do this," she said.

Our List of Essential Technology for Cruising the Bahamas

- Explorer Chartbooks by Monty and Sara Lewis

- Gentleman's Guide to Passages South by Bruce Van Sant

- Abaco, Exuma, and On and Off the Beaten Path guides by Stephen Pavlidis

- Cockpit mounted chartplotter

- EPIRB

- SSB Radio for weather, cruiser nets

- Polarized sunglasses for reading water color